ORIGINS OF BRITISH INDIA

Elihu Yale began his career with the East India Company as a clerk in the company's offices in Leadenhall Street in London. He was twenty one years old. In October 1671, he was chosen as one of twenty young men to go to India as a 'writer'. After a six month voyage he landed in Fort Saint George in June 1672. He would live in India continually until his return to London in 1699.

The East India Company had been founded on the basis of a charter granted in 1600 by Elizabeth I. Previously trade with the East Indies had been largely a monopoly in the hands of the Portuguese, but the war with Spain had cut England off from Lisbon. English merchants were obliged to buy at inflated prices either from the Dutch or from an English company which specialised in trade with Turkey. The charter given to the Earl of Cumberland together with 215 knights, aldermen and merchants, gave them the exclusive right among British entrepreneurs to trade in the area for fifteen years. In 1609, under James I, a new charter gave them the right to seize the vessels and cargoes of unlicensed traders at any point, whether subject to the British crown or not, within the limits of their commerce. This was a perpetual right, subject only to revocation by the King.

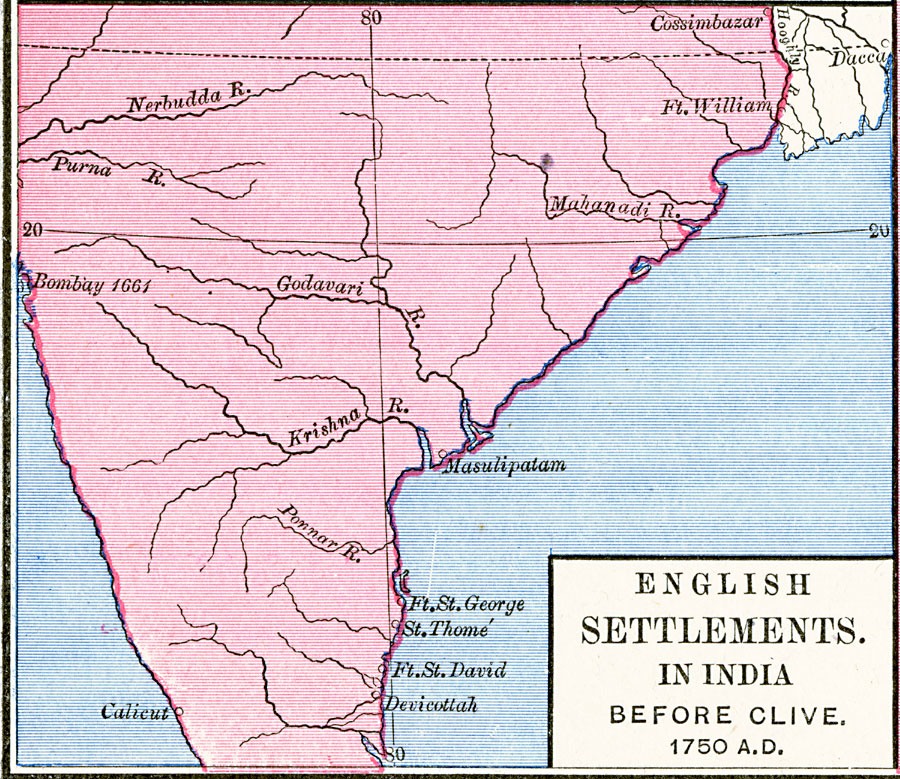

The trade had to be established in competition, often amounting to open warfare, with the Portuguese and the Dutch. The company also needed to negotiate rights and privileges with local rulers, both in India and to the East, initially in the area that is now Indonesia, which was the major producer of spices, a trade largely controlled by the Dutch. In India, the dominant power was the Muslim Mughal Empire, with its capital in Delhi. The English initially established a presence, against Dutch opposition, in Surat, a port in the Mughal territory, on the West coast of India. To the south of it, in the territory of another Muslim kingdom, Bijapore, was the main Portuguese centre at Goa. Further South again the English had a presence at Kozhikode, or 'Calicut', in a Hindu kingdom on the Malabar coast in what is now Kerala, in the extreme South West of India. This was a territory much disputed by the Portuguese and now under Dutch domination.

The English had also established themselves at an early stage in the seventeenth century in Bantam, in a Muslim kingdom in what is now Java. Cloth bought in India would be traded against the very desirable pepper bought in Bantam.

Fort Saint George, where Elihu Yale arrived in 1672, was on the East coast of India, called the Coromandel coast, and was part of the Muslim kingdom of Golconda. The English had initially had a 'factory' (as their trading stations were called) at Masulipatam, also in Golconda, but in 1639 they established Fort St George, south of Masulipatnam, as a place where the trade with Bantam could be conducted and defended 'from native insolence and Dutch malignity.' Fort St George was situated beside two villages, Madraspatnam (hence the English name 'Madras') and Chennapatnam (hence the modern Indian name, Chennai). At the time these were part of the territories of the Hindu Rajah of Chandragiri, who allowed the English to build a fort, establish a garrison, and to exercise judicial authority over the inhabitants of the small area that was under their control. Fort Saint George was close to the Portuguese settlement at Saint Thomas (where St Thomas the Apostle is said to have been martyred). Relations between the two were generally good, probably because of the common threat posed by the Dutch at nearby Pulicat. In 1646, the Rajah of Chandragiri was forced to flee when the area was incorporated into Golconda under the Nawab Mir Jumba, a diamond merchant, said to be the richest subject in all India. Golconda was known for its diamond mines. The English managed to maintain their privileges under the new regime.

In addition to the important factories at Surat, Calicut and Madras, there was a factory at Houghle, in Mughal territory in the North East, in the Bay of Bengal, at the mouth of the Ganges. Dependent on these principal factories was a variety of smaller agencies. When Charles II married Catherine, the Infanta of Portugal, in 1668, part of the wedding dowry was the island of Mumbai (Bombay) which soon replaced Surat as the most important English factory in the North West. Later, during a period of conflict with the Mughal at the time when Yale was in India, the factory at Houghle was moved to what was at the time the quiet village of Calcutta.

The East India Company was still far from being the great power it was to become. It was still dependent on the good will of the Indian powers, subject to terms decided by them. Under Charles II and James II, however, the idea was becoming established that wherever it was present the company should be able to exercise the rights of a sovereign power. This more aggressive approach, with the example of the Dutch East India Company in mind, was particularly associated with Sir Josiah Child, the dominant figure in the London-based directorate during Yale's period. One nineteenth century historian of the company, J.Talboys Wheeler, describes Child as 'the first man in England who seems to have formed a just conception of what ought to be the relations between the English and the Natives in this country.'

Robert Grant, in his Sketch of the History of the East India Company, gives a brief description of how the company functioned:

'Charles, by a charter dated the 3d of April, in the year 1661, not only granted them an ample confirmation of their former privileges, but conferred on them, within the limits of their trade, the power of making peace or war with any prince or people, not Christian; of establishing fortifications, garrisons, or colonies; of exporting to their settlements ammunition and stores duty free; of seizing and sending to England, such British subjects as should be found trading in India without their licence; and of exercising in their settlements, through the medium of their governors and councils, both civil and criminal judicature, according to the laws of England ...'

Particular areas were grouped under the same regulations - the Malay Islands, the Coromandel Coast, 'the portion of Persia on the gulf of Bussora' (Basra), and Bengal.

'The factory consisted of a number of buildings and offices; and, where the jealousy of the native potentate on whose territory it stood permitted, was fortified and garrisoned. Several servants of the Company, under one chief agent, were here stationed, and exercised a general superintendance over the commercial concerns of the Company throughout the whole division. Most of those concerns, however, were conducted immediately at the factory itself. Contracts were formed by the agents with the native merchants who, on receiving a certain advance of stock, obliged themselves, under pecuniary penalties, to deliver a given quantity of goods at a stipulated period. By this arrangement the Company were invested with a previous right in the goods for which they contracted; and hence their purchases in India have acquired the name of an investment. But, within the range over which the supervision of such a factory extended, there probably were many points where goods might be procured, and where, either on account of their distance, or for some local reason, it might be desirable that the purchases of the Company should be conducted immediately on the spot. To these points, agents were deputed from the principal factory; out of which, therefore, there grew, in this manner, a number of subordinate factories or agencies.

'These agencies were of various size and importance; in some cases, a single agent, with his native clerks and assistants; in others, an establishment, rivalling in magnitude that to which it was subject. Yet the agency maintained a constant correspondence with the capital factory, if that term may be used, and was guided in all its transactions by the orders thence transmitted. Instances of such principal factories with some of their subordinates are, Bantam with its dependencies, the smaller factories in the Archipelago; Madras, with its dependencies, Masulipatam, Madapollam, Pettipolee; Hughly, with its dependencies, Cossimbazar, Ballasore, Patna, Malda ...'

A number of reforms were introduced in the organisation of the factories from 1670 onwards:

'Of those provisions the most striking were, that the council should be chosen exclusively by the Court of Directors, or, as they were then called, of Committees; that the agents at the out-stations should not be removable by the presidency, except for misconduct; that regular minutes of all public proceedings should be kept and transmitted to the authorities at home; that certain prescribed forms should be observed in the correspondence with those authorities and that a general gradation, according to seniority, should be established in the service, the scale, both of rank and of emolument, ascending through the successive classes of apprentices, writers, factors, merchants, and senior merchants out of which last description of persons the council, at least that of the presidency, was, it may be presumed, usually selected.

'The factors and other servants were interdicted, though the interdiction did not always prove effectual, from such commercial dealings on their private account, as might interfere with the purchases or sales of the Company. But beyond this limit the prohibition never appears to have extended. On the contrary, not only were the servants freely allowed to embark in the coasting or country trade of India, but the importation of some commodities of great value into Europe was left exclusively to their private speculations; the imports being made in the ships of the Company, on payment of a small acknowledgement for freight. Such commodities, in the year l674 at least, were diamonds, bezoar-stones, pearls, ambergrease, and musk. In 1680, the Company resumed the trade in diamonds; yet even then, the servants were allowed a commission of five per cent on the purchase of the article, and also a proportion of the profit accruing on the sale in Europe.

'It is impossible, indeed, to account for the smallness of the salaries in the service of the Company on any other principle, than that the perquisites subjoined to them were considerable. On the reduction, in 1680, of the presidency of Surat into an agency, the annual salary allotted to the chief agent was £300; to the second in council , £80; to the other members of council in a declining progression, so that the lowest member had only £40; to the deputy governor of Bombay, the second person as to rank and authority in the service, £!20. Probably, a common table was at that time kept for the servants; but, with every allowance for this or other similar savings, and with an allowance also for the depreciation which money has since undergone in India as well as in Europe, the emoluments of the service would, from the scale given, appear most pitiful, unless we suppose that they were meant to be filled out by opportunities of private trade.'

The Governor of Madras when Yale arrived was Sir William Langhorne and his second in command, or 'book-keeper', was Joseph Hynmers, whose wife Catherine would later marry Yale. Minutes of the Council were kept by an apprentice, John Nicks, who, together with his wife, would later be a close associate in Yale's commercial affairs.